A Brief History of Deed Restrictions and Restrictive Covenants.

Racial covenants and deed restrictions at the turn of the century were used in a scattered, uncoordinated fashion until the 1910s. Then, a leading real estate developer began using and promoting deed restrictions. In the 1920s, a Supreme Court case removed obstacles to using restrictive covenants and their use spread far and wide.

Kansas City real estate developer J.C. Nichols began using deed restrictions on his Country Club District and promoted them to colleagues through the National Association of Real Estate Boards (NAREB). Such restrictions and covenants were certainly used before Nichols, but he helped spread and popularize their use on a large scale.

The use of restrictive covenants and deed restrictions grew in the wake of the ruling in Buchanan v. Warley in 1917. In that case, a racial segregation ordinance in Louisville, KY, was struck down by unanimous decision of the U.S. Supreme Court as a fundamental violation of property rights. Afterwards, individuals made private contracts and agreements in their neighborhoods, since legislation was not an option for imposing racial segregation in housing.

In Chicago, many suburban real estate developers followed J.C. Nichols’ lead and began putting restrictions on their whole subdivision at the time they were platted. The Chicago Tribune was filled with real estate advertisements boasting that a new subdivision was “highly restricted.” These restrictions often included minimum lot size, minimum home size, minimum setbacks, minimum home value, and they forbid the development of many kinds of land uses. These restrictions were race neutral while still being intentionally exclusionary for many immigrants, whites of the working class, and African Americans. However, these documents also included explicit racial restrictions that forbid the properties from ever being inhabited or owned by anyone not of the Caucasian race. These restrictions would “run with the land,” meaning that they would remain in effect even when the properties changed hands.

Real estate developers placed advertisements for their new subdivisions in the Chicago Tribune regularly. Just as regularly, the advertisements bragged that the new development was protected and “restricted.” In this case, these new metro Chicago developments were both “zoned and restricted.”

In 1921 in Washington, DC, a group of neighbors on S Street in northwest Washington circulated one of those agreements, a restrictive covenant, and dozens of neighbors signed it. The next year, a woman on the block had to sell her house and a Black couple contracted to buy it. The originators of the covenant stepped forward and sued the seller, Irene Corrigan, in a case that made its way to the Supreme Court. In 1926, the Court ruled in Corrigan v. Buckley that it did not have the standing to decide on whether the covenant was constitutional because it was an agreement between private parties.

The ruling opened the door to widespread use of restrictive covenants and deed restrictions. A year after the Corrigan ruling, Nathan MacChesney, the general counsel of NAREB, wrote a model covenant document based in part on the one in Washington, DC, and the real estate organization began promoting it to real estate boards around the country. With the tacit approval of the Supreme Court, there was little to stand in the way of covenants’ adoption.

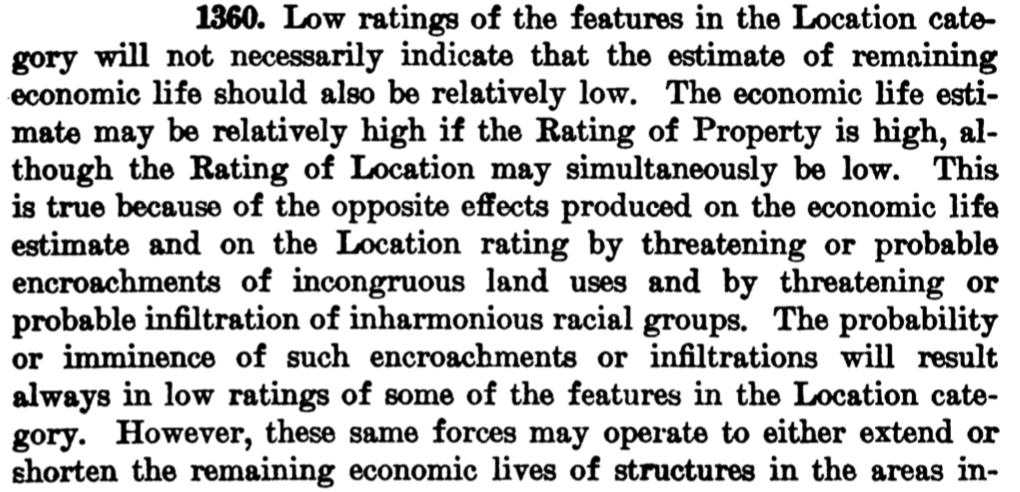

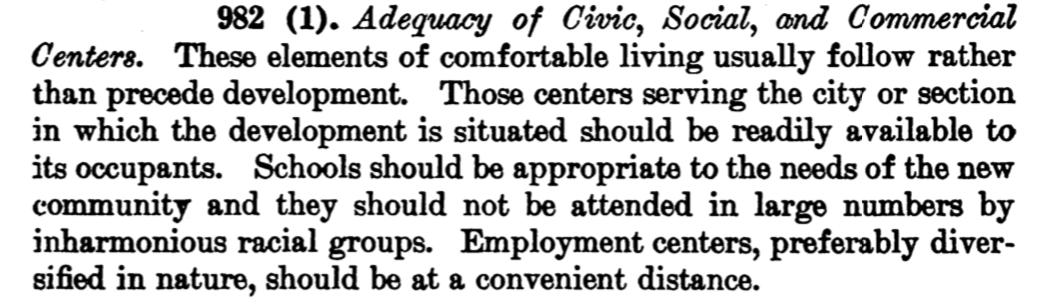

Deed restrictions and covenants, however, received the approval of the federal government in another form. When the housing sector reached a crisis during the Great Depression, the Hoover administration and the Roosevelt administration created new agencies to rescue the housing sector. Among these was the Federal Home Loan Bank, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation, and the Federal Housing Administration. These agencies created new practices and standards for home finance and real estate, and both HOLC and FHA emphasized and promoted the value of racial restrictions. In this way, redlining was in part built on the foundation of deed restrictions and racial covenants.

Two Kinds of Covenants

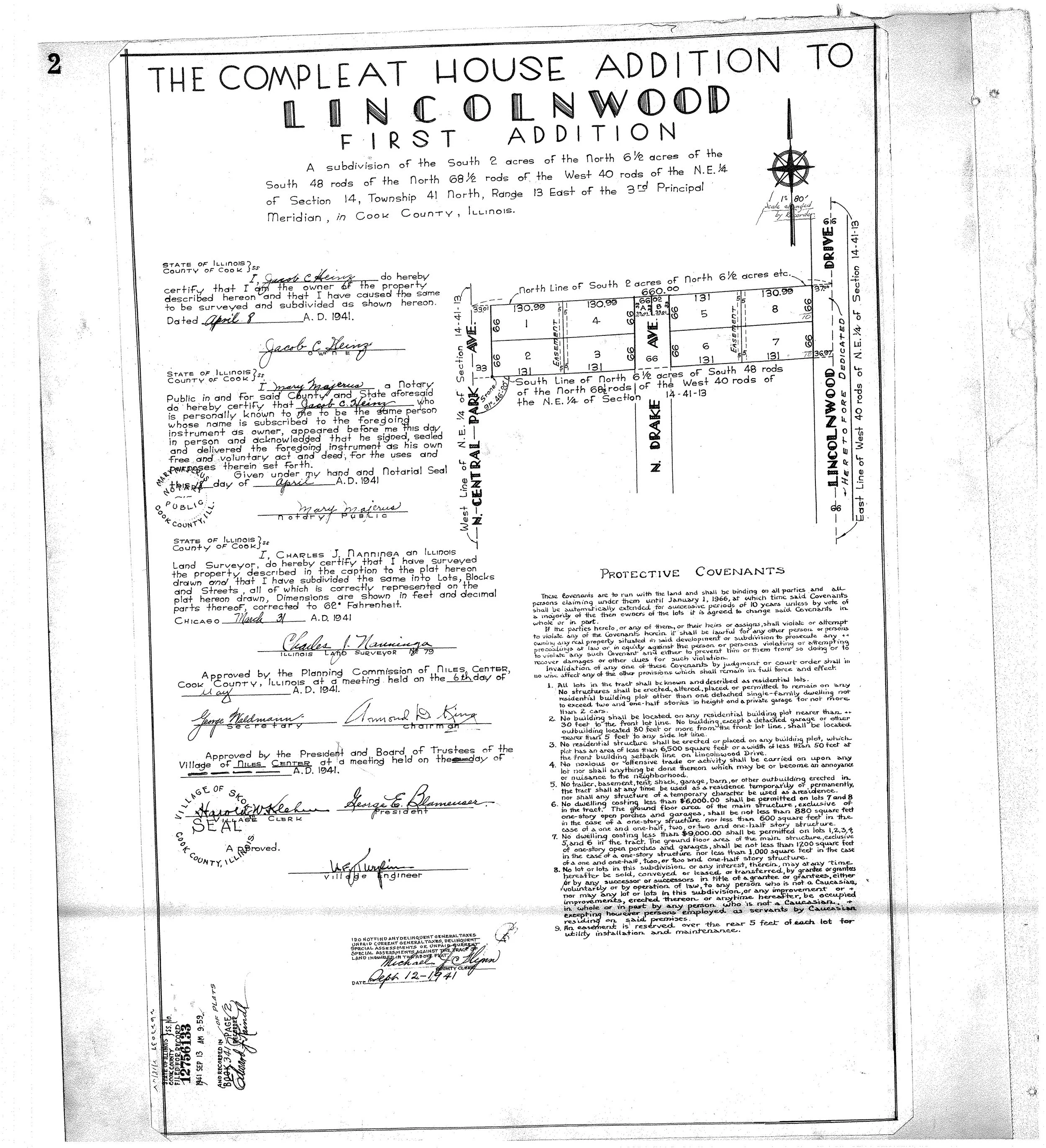

In Cook County, we find two main type of covenants: plat restrictions and agreement covenants. Plat restrictions are covenants created by real estate developers before a lot has ever been sold, when he or she files it with the County Recorder. They are often at the periphery of developed areas.

Agreement covenants are documents signed and filed by groups of neighbors in already-developed neighborhoods, usually much more centrally-located.

A plat restriction for a racially restricted tract in Niles Center, IL.

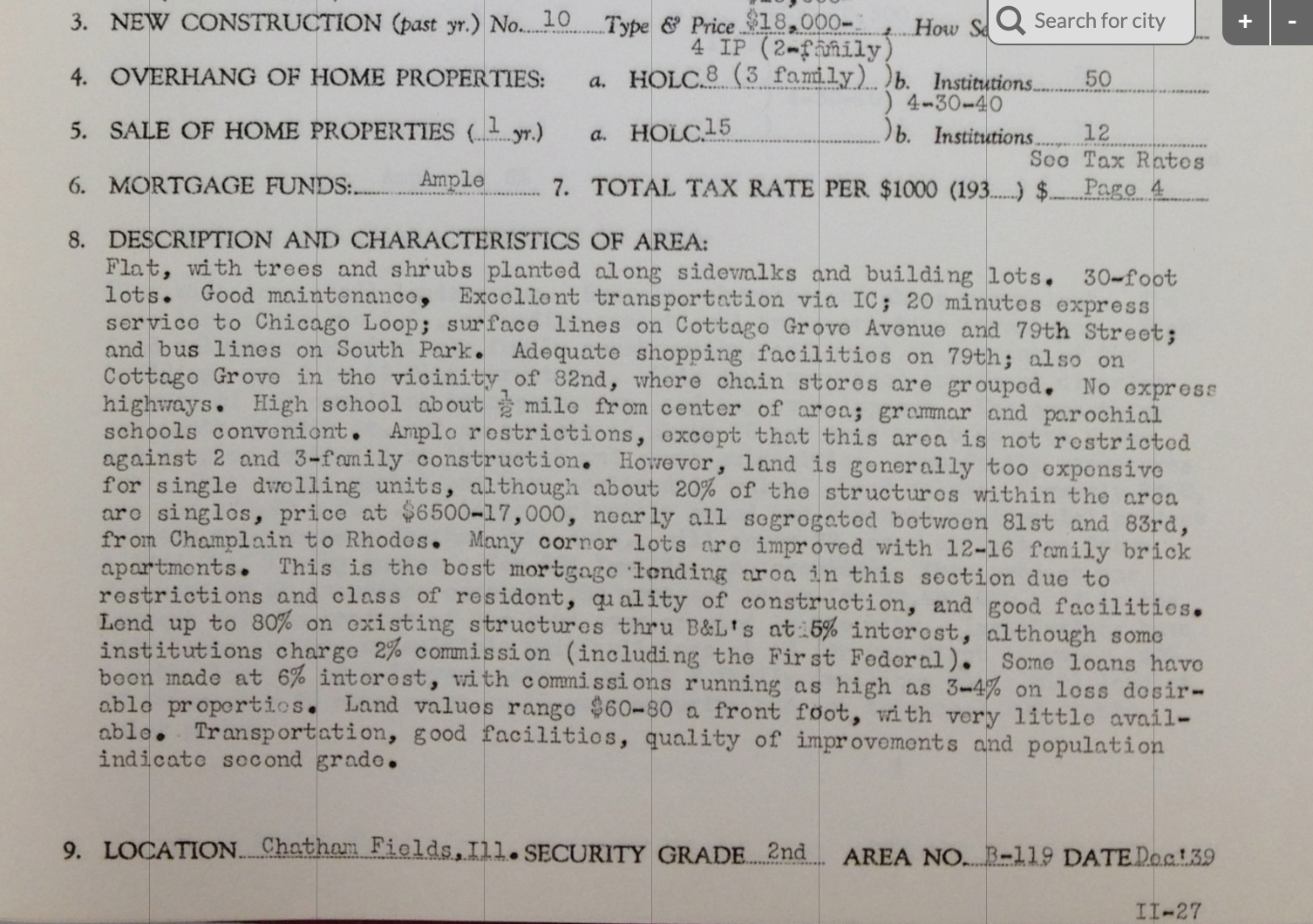

First page of racially restrictive clauses for an agreement covenant in Chicago, IL.

HOLC Area Description for a well-rated neighborhood.

Section on "inharmonious racial groups" from FHA Underwriting Manual

Section from Underwriting Manual on schools and inharmonious groups.

In June of1938, a whistleblower at the Brooklyn FHA office contacted NAACP official Roy Wilkins, to let him know that the FHA was not guaranteeing any mortgages that did not have a restrictive covenant. Wilkins contacted, Robert Weaver, a member of Franklin Roosevelt’s “Black Cabinet,” to try to assess this claim. President Roosevelt eventually denied this, but Robert Weaver began working with Thurgood Marshall and NAACP leaders to research and challenge covenants. This effort came together in the case Shelley v. Kraemer, in which the Supreme Court ruled in 1948 that restrictive covenants were unenforceable. This was the argument that NAACP lawyers led by James A. Cobb made in Corrigan v. Buckley in losing lower court efforts. Shelley was not a clear end to the use of covenants and restrictions, as they could still be used to shore up neighborhood bonds and solidify discriminatory tendencies. However, the fear of court order waned and city neighborhoods could be desegregated or could quickly flip from white to Black in a wave of panic selling.