Maintaining Clear Title Through Disaster

By Maura Fennelly

Nearly 3,500 property index books containing millions of property transactions sit in the basement of Cook County Clerk’s “Tract Department” where our biweekly research sessions take place. As our team of volunteers attentively comb through books to locate covenants, Cook County residents come down to speak with Tracts staff about the “chain of title” on their or their loved ones’ properties. Meanwhile, several title search employees work their way through index books and computer searches to create an abstract of title, which is necessary for getting title insurance that guarantees legal ownership of land. Why are covenant and title researchers working in the same space and interacting with the same analog county property records?

While there are some minor variations to how the 3,141 U.S. counties store property records in their “registries”, the overall system “is remarkably uniform across the country”, according to legal scholar K-Sue Park. Some county registries are digital, some are analog, and some, like Cook, are a mix of both. The purpose of registries is also uniform: to determine who legally owns a parcel of land. Index books note who the originator (grantor) and receiver (grantee) are for every transaction ranging from mortgage creations to racially restrictive covenants [1]. In his dissertation on the Chicago Real Estate Board, sociologist Everett Hughes found that real estate stakeholders need titles to be “secure and easily transferable. This condition depends on complete and accessible records”. Without the records, title companies cannot provide title insurance that provides protection against any unsettled defects [2].

The Cook County Clerk follows a similar system of tracking property transactions like other counties, but is unique in how it maintained its records through disaster. Without the forward thinking of private title companies, the County would have lost all property documentation spanning back to 1819 when Illinois established county recorders. Lawyer Edward Rucker came up with an efficient system to note property transactions more efficiently and joined forces with real estate developer James Rees to create the first title abstract business in the city. Three brothers joined Rucker and Reese to create Chase Brothers & Co., which along with Shorall & Hoard and Jones & Seller were the three main title abstract companies in Chicago that formed during the mid 1800s as real estate boomed and speculators desired clear ownership.

The location of the City-County building is covered by the red “burnt district” in the loop. While the building our research sessions are in was built in 1911, the location has been the same since 1853. (Source: Newberry Library, Chicago and the Midwest)

Yet clear ownership and legal protections were suddenly upended by The Great Chicago Fire. The 1871 fire destroyed almost all of the County’s real estate records as City Hall burned. The Chicago Times reported: “There has been absolute destruction of all legal evidence of titles to property in Cook County. The annoyance, calamity and actual distress that will arise from this misfortune are not yet properly appreciated. Something equal to the necessities of the case must be done quickly.”

Chicago City Hall 1871 pre- and post-fire (taken 5 days apart). (Source: Chicago History Museum, Prints and Photographs Collection)

In the immediate aftermath of the fire, there was uncertainty over how the rights to ownership would be upheld. Legal scholar and member of Chicago Title & Trust Company Walter Smith wrote in 1928, “As the destruction of the book containing the record does not destroy the legal effect of the record, every purchaser is charged by law with notice of what was contained in these burned volumes. As our Supreme Court said in a case concerning the destruction of the records, ‘The situation of owners of property in Chicago was appalling”’ [3]. The three title firms miraculously had their own copies of the property records, along with index books and abstracts of property transactions. For example, Lyman Baird’s real estate firm had a fireproof safe that kept the records in one piece.

Instead of using the moment of disaster to increase transaction costs from property owners, the three title firms pieced together their respective records. Walter Smith argues that “by combining their salvage they would have a complete set of all the necessary books, with some duplications, as well as letter press copies of a large number of abstracts theretofore made”. Yet the records alone didn’t guarantee legal title. Thanks to the three title firms’ willingness to reestablish accurate record-keeping, the Illinois legislature was able to pass the Burnt Records Act in 1872 (today it is known as the Destroyed Public Records Act), which meant that courts could use private companies’ property records to determine title ownership of properties.

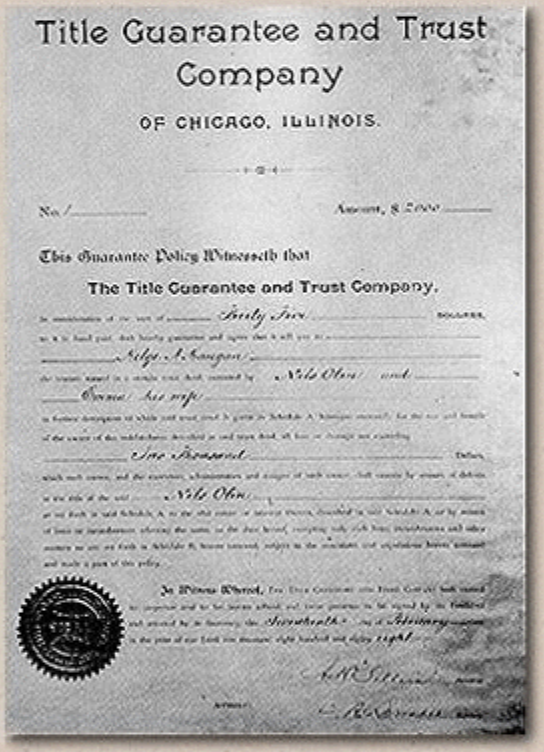

An example of a title insurance policy from Title Guarantee and Trust Company.

Without the collaboration between the state, title companies, and real estate industry to address the lack of documentation over “who owned what”, property owners across the city would have had to deal with extensive and costly legal battles. Instead, developers immediately began to rebuild the city and heeded the call from Chicago Tribune co-owner William Bross that “the people of this once beautiful city have resolved that CHICAGO SHALL RISE AGAIN.” Professor Carl Smith highlights how developers effectively rebuilt the downtown within two years, although fireproofing building codes didn’t go into effect until after a second smaller fire in 1874.

Perhaps influenced by the fire’s destruction, the Illinois legislature was the “first state to pass title registration law” called the “Torrens Title Act” in 1897. Real estate stakeholders embraced the new act because there would be a clearer record of who or what entity was the legal owner of the land so mortgages could be guaranteed. The Chicago Real Estate Board was a strong support of land title reform to speed up real estate transactions and:

“It advocates control of the use of land , as a means of giving to real estate values that stability and predictability which will enable the purchaser to know what he is buying. Not stability in itself, but in relation to investment and the market concerns the real estate agent. The Realtor is continually preparing land for the market, and is interested in whatever measures seem to facilitate its, marketability” (Hughes 1931, 85).

Just as the Board was advocating for racial covenants as a tool for stability in valuation, it also wanted title reform to create expectations that property would be protected through legal means [4]. Land titles continue to offer owners confidence in property ownership; racial covenants offered White owners a sense of assurance in property values. Both mechanisms focus on ownership as the legal right to exclude others from a parcel, or parcels, of land. There is much to be discovered within the nation’s property registries in terms of their idiosyncratic histories and “how registries themselves have been the site of struggles to determine who can own property and what ownership means” (Park).

Notes

In Cook County, covenant entries’ grantors read “[last name] et al.” and the grantee is blank because the agreement was between neighbors and not just between owners of one parcel.

Cook County uses both the Torrens system and the traditional title insurance method. The Torrens system originated in Australia and was most common in the County until the 1930s. Read more here.

Park notes that other county records have been entirely destroyed due to natural disasters or arson during the Civil war.

The Chicago Real Estate Board was fundamental in establishing and spreading racial covenants. The board instructed its members to establish property restriction associations so White owners would be deterred from selling to Black people. The board would expel realtors who did not obey.

Works Cited

https://www.ilsos.gov/departments/archives/IRAD/recorder.html

https://www.newberry.org/blog/the-house-that-survived-the-great-chicago-fire

http://www.encyclopedia.chicagohistory.org/pages/1262.html

https://www.ctic.com/history2.aspx

http://images.chicagohistory.org/asset/4335/

https://scholarship.kentlaw.iit.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1167&context=cklawreview

https://hdl.handle.net/2027/uva.x002089360

https://www.chipublib.org/fa-horace-g-chase-papers/