Racial Covenants in the Chicago History Museum Archives

By Hannah Simmons

Going through an archive is like embarking on a time-traveling expedition. Opening box after box and carefully fluttering through worn documents, you are greeted with an image of the past and a clearer understanding of present circumstances. Going through the archives in the Chicago History Museum’s Abakanowicz Research Center is no different. The volume of sources the collection holds is breathtaking, and the image of racially restrictive covenants it paints is striking. For example, in the Abakanowicz Research Center’s collection on the Auburn Park Property Restriction Association, one finds the story of John Frederick Wagner.

Born in Chicago on August 28, 1878, to German immigrants, William Wagner and Mary Nachel, John Wagner went on to become a lawyer and marry Eleanor Siebert. By 1910, John and Eleanor Wagner lived in the then all-white, majority second-generation European immigrant neighborhood of Auburn Gresham on the far Southwest Side. From all accounts, John Wagner was an everyday individual. However, on August 9, 1929, he entered the archival records.

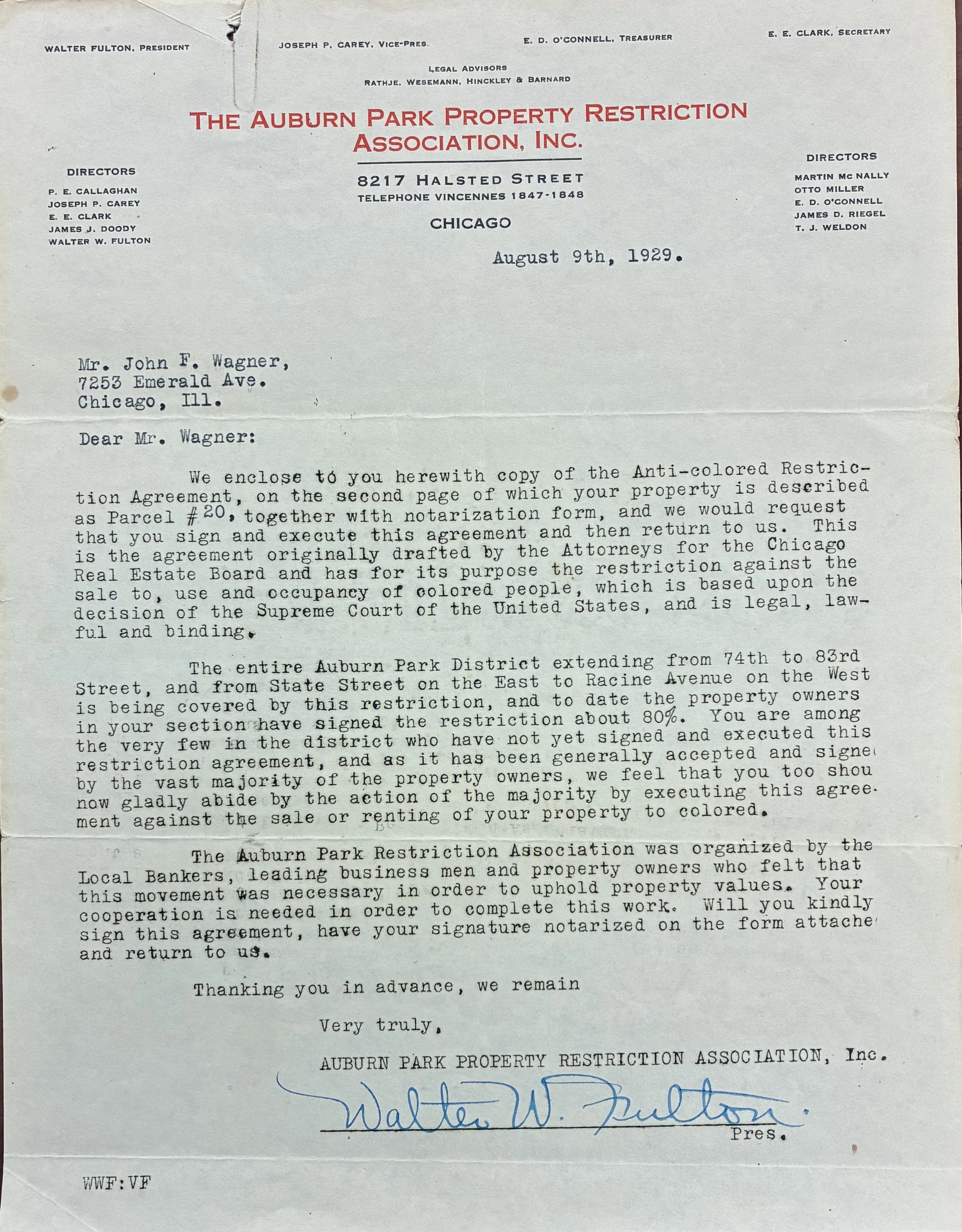

On August 9, 1929, Wagner, who had been living in Auburn Park for nearly two decades, received a letter from the Auburn Park Property Restriction Association. In the letter, the Restriction Association wrote, “the entire Auburn Park District extending from 74th to 83rd Street, and from State Street on the East to Racine Avenue on the West[,] being covered by this restriction, and to date, the property owners in your section have signed the restriction about 80%. You are among the very few in the district who have not yet signed and executed this restriction agreement, and as it has been generally accepted and signed by the vast majority of property owners, we feel that you too should now gladly abide by the action of the majority by executing this agreement against the sale or renting of your property to colored.” There is no indication why Wagner had not signed the covenant. However, two things are clear. First, most neighbors in Auburn Gresham had signed a racially restrictive covenant. Second, there was pressure on Wagner to do the same. Attached to the letter was a copy of an “anti-colored restriction agreement” for Wagner to sign. According to the agreement, the purpose of signing was to keep the neighborhood all white by prohibiting the sale of any property to all persons having “one-eighth part or more of negro blood.” Restriction agreements like the one Wagner received are a small part of the larger history of racially restrictive covenants in the Chicagoland area. The Abakanowicz Research Center has sources detailing this history.

Letter from Auburn Park Property Association to John Wagner, August 9, 1929.

The Abakanowicz Research Center has four known racially restrictive covenants, one from the Near North Side Property Owners’ Association to the Chicago Historical Society, asking the Society to sign a restrictive covenant, a letter from the Woodlawn Property Owners’ Association, thanking a property owner for their due payment that would help keep “Woodlawn to white people,” one from Auburn Park Property Restriction Association, and one in the Archibald J. Motley collection from the Englewood Property Restriction Association. While these are the known covenants, there are certainly more in the collection. For example, while going through the papers of the local real estate company, Baird and Warner, one finds mention of a building under covenant in Old Town. This mention of the building under covenant shows that while institutions and individual neighbors signed covenants, some of the main enforcers were real estate companies.

The boundaries of the Auburn Gresham (bottom left), Englewood (top left), and Woodlawn (top right) neighborhoods.

Real estate companies, like Baird and Warner, promoted covenants based on the idea that if Black people were allowed to buy property, property values would go down, the area would become blighted, and would eventually turn into a slum. In a pro-covenant paper simply titled Restrictive Covenants (July 1944), found in the Bowes Realty Collection, the Federation of Chicago Neighborhoods lamented how unjust it would be for white soldiers to come back from war to find that their “homes have been taken over by negroes” and their old neighborhoods were now slums (15). The paper made no mention of how Black soldiers would feel coming back to housing discrimination. However, continuing to comb through the archives, particularly the Catholic Interracial Council (CIC) archives, one sees that Black Chicagoans and their allies, like members of the CIC, did not simply accept racially restrictive covenants; they pushed back against covenants and the segregationist logic that covenants were entrenched in.

In an impassioned letter in the CIC records, a Chicago Servite missionary, and regular author for the Novena Notes column, Father Hugh Calkins, O.S.M., was credited with stating, “Let white families stay and live together like Christians with Negroes. Either you admit they are equals or you don’t. If you don’t, you profess Hitler’s doctrines, branded false by science, forbidden by the inspired word of God, condemned by the Pope.” This powerful condemnation of racial segregation shows that there was a severe problem with segregation in housing in Chicago, which covenants exacerbated. After years of people like Father Calkins decrying the unconstitutional, undemocratic, and immoral nature of covenants, in Shelley v. Kraemer (1948), the Supreme Court decided that racially restrictive housing covenants could not be enforced. This was a blow against covenant makers and enforcers and a win for those who pushed back against covenants. Whether through fervent writings like Calkins or through the African American-promoted Double-V campaign (victory over fascism abroad and victory over racism at home), one sees that people questioned and pushed back against the logic, morality, and legality of covenants.

Racial covenants were, and are, hidden in plain sight. These documents were so prevalent that we can find them throughout land and historical archives. While we can see that these quotidian, legal instruments shaped housing in Chicago, we can also see how Black Chicagoans, and their allies, attempted to reshape housing in Chicago, attempting to unravel the harm covenants caused. Discussing the prevalence and pushback against racial covenants is crucial, and the archive makes it possible to tell both sides of the story.

Hannah Simmons is a 2025-2026 Black Metropolis Graduate Assistant, working with the Chicago History Museum and the Chicago Covenants Project.